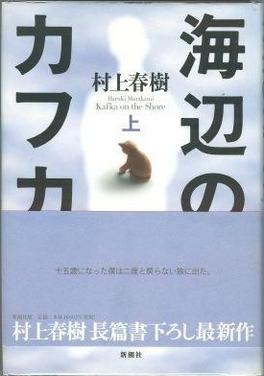

Kafka on The Shore (lit. Umibe no Kafuka) is the tenth novel by author Haruki Murakami, first published in Japan in 2002 and translated into English three years later by Philip Gabriel, frequent Murakami translator. Its 2005 English version was featured on The New York Times list of ’10 Best Books of 2005′ and it even received the acclaimed World Fantasy Award in 2006. Consisting of 505 pages, it treads the middle ground between a long Murakami novel and a short one, though it leans towards the former.

Organized in a format unusual to the majority of his other novels, focus is placed on whether each chapter is an odd or even one, as two distinct but connected storylines take place depending on this chapter layout. The odd-numbered chapters chronicle the journey of 15-year old Kafka, who runs away from home on a quest to find his missing mother and sister, while picking up several allies along the way. The even-numbered chapters showcase the perspective of Nakata, an illiterate elderly man with the ability to talk to cats, who finds himself far away from the comforts of his home. As the story continues, the plot deepens: Kafka is questioned for murder, Nakata tracks down a cat killer, and plot points thought to be random and inconsequential turn out to hold the biggest clues of all.

I’ll admit, I have a bit of bias towards this particular book, namely because it was the first piece of fictional Murakami I read (not the first – that would be Underground, but that’s for another Monday) and it was the reason I found myself so drawn into his work, not to mention it introduced me to the ‘magical realism’ genre. I still enjoy it after all these years, surprisingly. The characters are interesting, the moments of ‘magic’ feel magical, and the story is one of the better-paced ones. Overall, I highly recommend it, for Murakami fans, non-fans, and fans of a good surreal fantasy story alike.